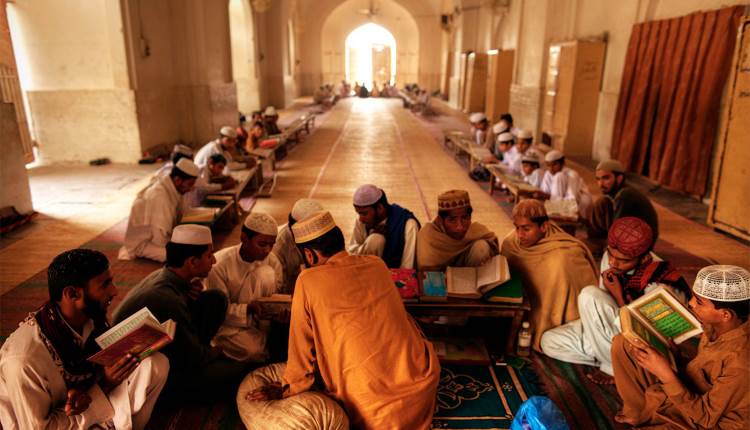

The Call for Madrassa Reforms

The Pakistani parliament has recently been involved in the debate surrounding the reformation of Madrassas in Pakistan. For this purpose, the government has setup an investigation team to examine the existing methods of teaching and curriculum followed by these seminaries. The high importance attached to this investigation stems from the fact that a cleric’s function in a Muslim society is pivotal: They are perceived as guardians of the Quran and Hadith. They derive great authority and following from being the custodians of religious knowledge and have the ability to shape and mould minds and hearts of millions of people. The government felt it is its responsibility to ensure that these sources of authority pass through a certain rational process of education before they practice their clerical functions. However, this endeavor by the government wasn’t taken too positively by some of the religious establishments and was seen as encroachment on their exclusive domain of authority. What they failed to acknowledge was that the government had the right to inspect the functions of these institutions like it had the right to in case of all other units functioning in its domain of authority. If they were to resist and not co-operate, it would amount to challenging the writ of the state and would then have to be dealt with accordingly.

In order for these reforms to make inroads and bring about change, it is absolutely necessary for people to feel, realize, and understand the need for such reforms. Change can only be effective if it is felt from within. If the perception amongst the public is that the cause of reformation is some outside source, the United States, then the true outcome of such reforms cannot be actualized.

How to bring about change in the existing Madrassas? I propose tackling the problem at two fronts. The first important, yet drastic, measure should be the eliminating of the first 12 years of the existing education in these Madrassas and replacing them by a broad-based education system that is no different from what is being taught to all other young people of the country. A child at the tender age of five does not have the reasoning ability to think critically; to entrust him to such institutions with a decision that he is destined to become a religious scholar is a unique and absurd way of creating specialists. Young men and women should get the opportunity to choose independently after they complete twelve years of broad-based education, like they do in any other profession. Why isn’t Religious Studies in Madrassas treated like other disciplines? It is a matter of human rights. The government has the right as well a duty to take away the authority to impart specialist education to make scholars from the age of five years. It is only at the age of seventeen, or after twelve years of broad-based education, that a young individual should be given the right to choose his or her career. If innocent children are being forced to become scholars without them even realizing it, the government should intervene to undo the process.

Another important policy reform should be to ban the affiliation of any religious group to any Madrassa. The labeling of Deobandi, Shia, Brailvi, Ahle Hadith, and Jama’ate Islami Madrassas should come to a stop and the focus should rather be towards imparting higher quality education to the students than on injecting a one-sided point of view that only fuels sectarian bigotry if not tension and violence. Do we allow only Classical, Neo-classical, Keynesian, or Marxian Economics to be taught in institutions specializing in these schools of understanding? Why do we allow such an absurdity to flourish in our religious seminaries? I, therefore, suggest a diverse faculty, encompassing a range of scholars from different religious orientations, exposing a plethora of ideas to the students. This will not only broaden the horizon for these young students but will also allow them to respect and tolerate people with different views and beliefs.

Is it realistic to expect that such reforms would see the light of the day? Are the Madrassas ever going to be ready to accept such proposals? Very unlikely! However, we mustn’t lose hope. If we are able to construct a system parallel to the existing one, I’m hopeful that change can be brought about. If we are able to establish new institutions that incorporate the policies and suggestions that I have put forward, I’m positive that the new crop of scholars produced by it will be more appealing to the masses. With a proper base, I don’t see why the Madrassas won’t die a silent death.