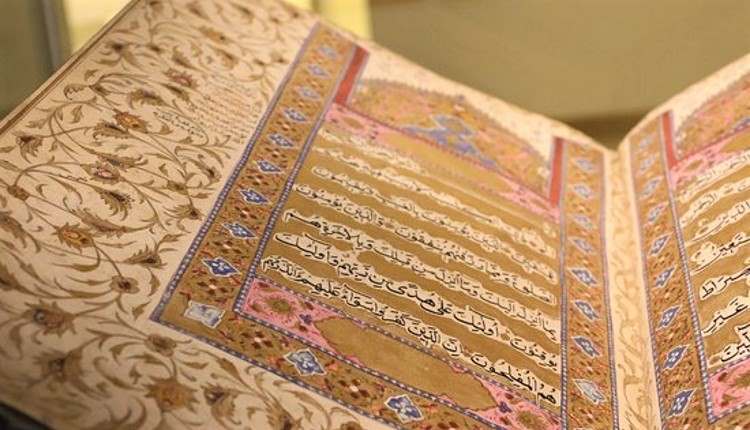

Is The Quranic Text Coherent?

For one to be convinced about the brilliant manner in which the Quranic wisdom hidden in its thematic and structural coherence unfolds itself one needs to critically reflect upon its verses with attention

The Quran claims that it is a book of guidance for the mankind; it emphasises that its message is clear; it stresses that its teachings distinguish unmistakably right from wrong; it declares that its contents are guarding the earlier books too; and it requires believers to hold fast to it if they were to remain united. Can such a book be a jumble of unrelated statements randomly put together? Can it be forced to seek support from the crutches of other sources for its message to be understood? Obviously not. In order for the Quran to be shown as a coherent book, however, the wise marshalling of its verses and chapters needs to be shown in a manner that the book should itself speak out to the reader that its contents form an elegant structure of pearls of wisdom and not a mere jumble of white marbles scattered across to form a hopelessly indiscernible heap.

Luckily that task has been initiated in a promising way by a group of scholars whose third generation is now expending its energies to continue to further the immensely important project initiated by master pioneer of it, Hamiduddin Farahi (d. 1930). His illustrious student, Amin Ahsen Islahi (d. 1997), took over from his mentor to transform the idea into a reality in his exegesis, Tadabbure Quran (Reflecting upon the Quran). Islahi’s student, Javed Ahmad Ghamidi (b. 1951), has completed writing his annotated translation, al-Bayan, adding further refinement to the basic idea initiated by Farahi.

In order for the Quran to be shown as a coherent book, however, the wise marshalling of its verses and chapters needs to be shown in a manner that the book should itself speak out to the reader that its contents form an elegant structure of pearls of wisdom and not a mere jumble of white marbles scattered across to form a hopelessly indiscernible heap

According to the research undertaken by these scholars, Quranic coherence unfolds itself at three levels: surah unity, surah pairs, and surah groups. Each surah (chapter) of the Quran has a thematic scheme that is so meticulously followed by all its verses in a way that none deviates from it. Most Quranic surahs have been positioned in a manner that two adjacently appearing ones form pairs. And the entire Quran is divided into seven distinct cohorts, each beginning with one or more Makkan (pre-Hijrah) surahs and ending with one or more Madinan (post-Hijrah) surahs. Each cohort (or what is described as group) has its own scheme of presentation.

Let’s take the idea of surah unity first. Contrary to the popular view and the apparent impression one gets on reading the Quran cursorily, each surah works out contours of its beautiful picture by involving the different shades of its passages. One passage flows from another meaningfully to chart out a journey of ideas that, put together, make a fully integrated theme. The example of the second chapter, al-Baqarah (the cow), by far the largest, might help. Several in-depth readings of the chapter would reveal that the two hundred and eighty six verses of the chapter are divided into three parts: a prelude, an address to the Children of Israel, and an address to the Children of Ishmael. When the chapter moves from the prelude to the first of the two addresses, thematic coherence of the text is seemingly threatened. The story of Adam and Satan is followed by an appeal to the Children of Israel to have faith in the Quran and the messenger, God’s mercy be on Him. The shift is apparently sudden and, to begin with, inexplicable. But a deeper reflection unfolds a scheme of ideas wherein the Children of Israel were being informed about the imminent obstacle in their way of accepting the truth that had come to them from God: false sense of superiority bordering on arrogance that was the moral of the story of Adam and Satan. Thus the story preceding the invitation to the Children of Israel made good sense. In the same vein does the surah flow from one passage to another to complete the journey of the message it carries. Likewise are fully coherent all other surahs of the Quran, big or small.

The presence of surah pairs is another remarkable feature of the Quranic coherence. Except for six surahs, the rest of them form fifty-four surah pairs in a way that each partner of the pair contributes to the common theme, like any two partners would complement each other in a joint project. Balanced family life, for example, is the common theme of the pair of surahs 65 and 66, Talaq and Tahrim respectively. The balance gets challenged when either attachment with family members exceeds acceptable limits or when relations threaten to break, reason giving way to anger. While surah Talaq deals with the issue of anger crossing limits, surah Tahrim deals with the issue of love of family members exceeding limits. A serious reading of the rest of the fifty-three pairs reveals similarly remarkable affinity in the themes of the surahs partnering to form pairs.

Perhaps the most daunting task in bringing together the seemingly disjointed pieces of the Quran is to explain meaningfulness of its complete structure: Why have the hundred and fourteen surahs of the Quran been sprayed across with utter disregard to their chronological order? While the challenge is seriously threatening, the response to it is thankfully appealing. It is not a random scattering of surahs but a very well thought arrangement of them that has caused the surahs to be placed in the existing Quranic arrangement to form seven meaningful surah cohorts or groups. The second group (surahs six to nine) is probably the simplest to explain. Bound by the common them of explaining that the messengers of God prevail and their enemies doom, the group’s four surahs set about the task of achieving that goal by describing the theme of invitation extended to the pagans of Arabia, warning them, preparing believers to become God’s tools for inflicting His punishment on the enemies, and punishment finally reaching those enemies. The four steps completing the mission have been achieved by surahs Anam (6), Araf (7), Anfal (8), and Taubah (9) respectively.

For one to be convinced about the brilliant manner in which the Quranic wisdom hidden in its thematic and structural coherence unfolds itself one needs to critically reflect upon its verses with attention. The Quran says: “Do they not ponder over the Quran or is it that their hearts have been locked?” (47:24)

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

“The article by Dr Khalid Zaheer was published at dailycapital.pk on 13-MAR-15.”